As the end of Phase 1 of SAMSET passes, Simon Batchelor reflects on the important lessons he has learned from the programme of work.

I have worked in development for more than 30 years. Grey hair and aching joints mean that I have experienced some of the highs and lows of development work. Those times when a programmes contribution to development is washed away by a change in government, or times when simple ideas have grown to become policy and lift many off the poverty line. Times when I have worked with governments and times when I have sat with communities, lived with the people.

And yet to me SAMSET brought new insight. I would like to tell you why.

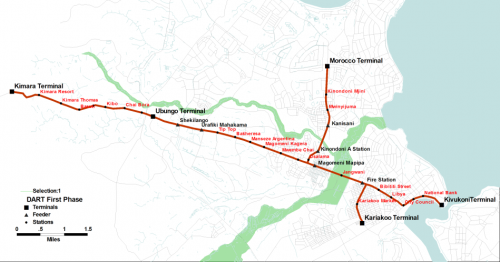

Municipality authorities – strange as it may seem, this was a level of governance that had passed me by in my career. Admittedly I worked a lot in rural areas. Back in the eighties when I started, everyone described Africa as dependent on agriculture, and rural livelihood improvements were the key. So I worked with ‘district’ authorities but not so much with municipalities. Now Africa has changed and will continue to change rapidly. Urban environments are the key challenge. Creating a space for urban based livelihoods, with all the complexity of transport systems and energy consumption. To me the municipal partners (in Awutu Sena East and Ga East Ghana; Jinja and Kasese Uganda, and Polokwane and Cape Town South Africa), have been a delight to work with. And consistent – they attend meetings and the same people attend meetings! How many times have I spent in my career developing a relationship with a government official only for them to be moved into a different ministry? And they take action – seeing some easy wins they have the authority to change building regulations or advice, and to purchase clean energy street furniture. There are indeed capacity challenges within municipalities, and indeed all the country wide problems of corruption are also within their processes; but when I consider some of the people I have worked with over the years, I say that our municipal partners were a delight to work with and I think we managed to achieve a great deal as a research project.

30 year time horizons – it is a sad reality of the development sector that people work in three or five year projects. Even large national programmes still set unrealistic targets in unrealistically short time spans. In SAMSET we have worked with municipalities to collect data, model it for population growth over 30 to 50 years, and then discussed the future. (For example Ga East LEAP Modelling Technical Report (ERC) (2017) and Jinja LEAP Modelling Technical Report (May 2017) (ERC). Our partners have considered what action they needed to take now to do something other than business as usual and to generate different futures for their cities. To some people the idea of thinking 50 years into the future is difficult. They say the pace of change of technology is such that we cannot know what it might look like. And yet at the same time others will argue that we have to. That the longer term visionaries are the ones who take small steps now which shape that technological change and address the environmental concerns (eg. Awutu Senya East Municipality Energy Futures Report 2015 (October 2015) (UoGhana)). It is true that self driving cars may change the shape of our cities. But it is also true that most cities in Africa will double in size within 10 years (due to population growth and inward migration). In SAMSET the municipality partners ‘stepped up to the plate’ (a baseball metaphor), and took a swing at looking at the future and taking action for the longer term future. For me this stood in contrast from so much experience of short term projects.

Evidence based decision making – has become a common phrase and yet in reality there is little actual data and what there is is rarely used. That’s why SAMSET was encouraging in my eyes. It started with data gathering. Not an easy task – to get granular data for a municipality means going and measuring it in partnership with the municipality. National statistics are too large too lumpy to enable municipal authorities to make sensible decisions for their own location. They tend to rely on feedback from citizens and staff to decide what to do. So to actually go and get the right data for making decisions was to me a great step forward.

There are probably other things that have made SAMSET noticeable in my eyes, but these are the three that come to mind as I sit to write this. If all my future projects had a sensible long term horizon, a level of governance with consistency in its personnel and an ability to reflect and act, and was willing to gather the right evidence in order to make a sensible decision – I would be happy.