Hlengiwe Radebe from SEA writes on energy poverty issues affecting peri-urban communities in Polokwane Municipality.

According to Statistics South Africa (StatsSA) Polokwane municipality, capital of the Limpopo Province in the north of South Africa and a SAMSET partner municipality, is 40% urban and 60% rural. In South Africa, most rural areas have basic service delivery challenges, and are still under the authority of traditional leaders. Part of the function of traditional leaders is to allocate land for new settlement. This traditionally-owned land does not have a typical market value and is usually far cheaper than land in urban areas.

Although 60% of land is described as rural in Polokwane, parts of the rural areas in Polokwane are transitioning from rural to urban areas (peri-urban), presenting a particular set of challenge to urban development. Some degree of agriculture still persists, but most people residing here are already dependent on urban jobs or grant payments. As part of urban municipalities, these areas have access to electricity, piped water and what one may call semi-adequate infrastructure. However, as ‘traditional land’ households are not part of the municipal rates and taxes system, presenting fiscal challenges to municipalities providing the services. Given that the land cost is very low, there is a strong incentive for the working municipal residents to obtain land and build in these outlying, but semi-serviced areas, rather than purchase expensive land in the urban areas. This does not lead to efficient settlement structure and increases the cost of servicing residents, including with adequate public transport.

An example of a house in Dikgale (Image: Alberts, M. et al (2015))

A good example of this situation is Ga Dikgale community in Polokwane municipality. Ga Dikgale has a population of 36000 residents in 7000 households. Dikgale is found approximately 40 kilometers north-east of Polokwane. The population lives in dwellings that range from shacks to brick houses. Mostly people are of Paedi ethnic group, all-African, and are an ageing population. The majority of the populace is economically disadvantaged in an area characterized by high unemployment rates, poor road infrastructure and poor service delivery. My visit to Dikgale brought back childhood memories – a sense of community where people could still walk to their neighbours and ask for salt or mealie meal.

A recent household energy survey (funded by Brot) conducted in partnership between Sustainable Energy Africa, University of Limpopo and Polokwane Municipality, covering 388 households in Dikgale, showed that 98% of households are electrified. The has been made possible by the South African government, that made a strategic decision to electrify all South African households both rural and urban, informal and formal, post the first democratic elections in 1994. This successful and globally leading National Electrification Programme was funded by national grants. As of 2016, according to Statistics South Africa, the South African government had electrified 91.1% households both in rural and urban areas although electrification rates in urban areas are significantly higher than in rural areas.

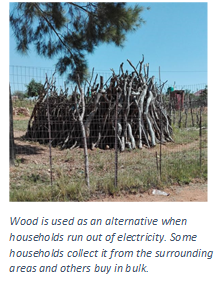

The survey revealed that electricity is indeed the primary energy source for household lighting, cooking and heating in most Dikgale households. Interestingly, in the area electricity is often referred to as “mabone” meaning light, as many households use the electricity for mostly lighting purposes. The survey indicated that wood is the secondary source of energy most commonly used for cooking, water and space heating. This is because households often run out of electricity due to lack of money, once their monthly Free-Basic Electricity (FBE) allowance provided by the municipality is used up. Other key energy challenges emerging from the survey in the area were:

- Lack of awareness around the Free Basic Electricity grant: This grant promotes the Constitutional right of all South Africans to modern, safe energy services, and provides indigent households with the first 50 – 100 KWh free of charge (Eskom supplied areas are provided with 50KWh and the municipality supplied areas receive 100KWH). The survey indicated that, of all of the indigent households, far too few are registered to receive the FBE grant from the municipality;

- Houses have no ceilings and corrugated iron roofs: this reduces the thermal performance of the house significantly. Houses without ceilings are colder in winter, where outdoor nighttime temperatures often drop to around zero degrees, and hotter in summer, where outdoor daytime temperatures of 30 degrees and above are common;

- Lack of awareness around energy-saving options such as the ‘wonderbox’. A wonderbox, also commonly known as a ‘hot box’, is an insulating bag which holds the heat of the pot after boiling and thus reduces the amount of fuel needed to cook the meal, lowering energy costs. This works with most common meals, such as ‘pap’ (a traditional porridge made from mielie-meal), samp, beans, rice and stew. (Image: Marole Mathabatha)

Having identified the above challenges, Polokwane Municipality and other municipalities in similar situations can address the current energy needs of peri-urban communities more effectively. From the Dikgale household energy survey, it appears that alternative energy approaches can reduce costs, improve comfort levels and reduce the use of traditional and other problematic energy sources, with associated pollution and environmental degradation improvements. Even where FBE is delivered to indigent households, this is not enough to keep households going for a month. Alternative technologies such as solar lights, wonderbox, tshisa box (a 10 litre portable solar kettle) and solar cookers are some of the technologies that could benefit households. They may also create small business opportunities in the area. However, the past has taught us that community acceptance of such technologies thoroughly needed for any rollout to be successful. Social acceptance factors are not easily understood without trying them out in practice.

Access to modern, safe and reliable electricity is a key challenge in many African countries. Peri-urban areas can sometimes fall through the cracks – not being adequately addressed by either urban or rural service delivery programmes. Polokwane municipality, in partnership with Sustainable Energy Africa and a steering committee of key stakeholders, is pioneering a rollout of alternative services, starting with hot boxes that will be made locally as part of a small business development initiative. How Polokwane deals with these challenges and this pilot project could provide useful lessons for other municipalities in improving energy delivery to low income households.

3 of the 5 young women from Ga Dikgale running a small business producing hot boxes (Image: Hlengiwe Radebe)