Johnathan Silver from Durham University highlights the flaws and limitations of current carbon financing mechanisms, and the pressure they put on an African continent at the forefront of climate change.

Even though sub-Saharan Africa has contributed little to historic Green House Gas emissions, a burgeoning body of research is pointing out that the continent is on the frontline of climate change dynamics and as a result facing multiple infrastructural pressures across an urbanising region.

It is an issue that is of concern to African leaders with the Vice-President of Tanzania, Mohamed Gharib Bilal expressing reservations at the recent ICLEI Local Climate Solutions conference in Dar es Salaam. In the opening session of the conference, he argued that the global response to climate change must be fair, reflecting common but differentiated responsibilities that would put the emphasis on industrialised countries to finance a low carbon urban future and support the separation of growth from carbon and wider resource intensity in African cities. Yet these commonly held views on the continent and beyond seem to be having little effect on the slow, painful process of financing low carbon infrastructures and a green economy in Africa.

This climate change driven, energy, resource and development crisis is not some imagined future but rather taking place in the here and now. Reflecting on these relationships between climate change, low carbon imperatives and infrastructure geographies from across urban Africa generates a critical question: Where is the financing coming from to transform energy systems that respond to low carbon and developmental objectives and fund the plethora of strategies and plans proposed over the last decade?

The prognosis is not an optimistic one. The failure of historic polluters to offer the necessary finance, technology transfer and solidarity highlighted by the Tanzanian Vice President as crucial to a low carbon, resource efficient urban future is achingly visible. The options out there now for African cities limited, full of contradictions and characterised by the dominance of carbon markets. Speakers at the ICLEI conference sought to help city policy makers navigate the Byzantine nature of market-based carbon financing, used (rare) case studies of success stories for the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and sought to draw some hope from a thoroughly discredited financing system. Yet these voices seem to be a minority as a growing consensus rejects the market rationalities embedded in carbon financing with a coalition of activists, academics and policy makers highlighting what seems like an endless number of problems with financing mechanisms such as the CDM.

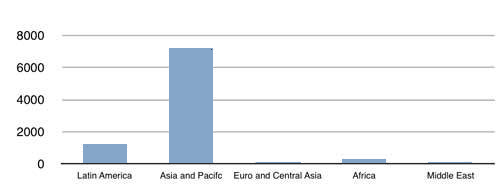

These critiques of carbon financing cover a series of issues from the privatisation of the air and the atmospheric commons through to the non-linearity of climate change. The almost perverse notion that polluters are being rewarded under these market conditions, together with widespread examples of fraudulent behavior seems to reflect the wider flawed logic of relying on the market and corporations to address socio-environmental conditions. Work by researchers in cities such as Durban show that cities with carbon market-financed projects are often positioned around mega-sized waste to energy technologies that are having devastating social and ecological consequences for local communities. Price fluctuations, speculative behaviours and the post-2008 crash of the carbon price have illustrated that these mechanisms are even failing on their own (market) logics and terms, reflecting the wider contradictions of global financial markets, derivatives and such like. Beyond these extensive general critiques there are some very real distribution inequalities to the current financing across carbon markets that suggest even if these wider flaws didn’t exist then this form of financing would marginalise African cities in these global flows of infrastructure investment. Taking the CDM as an example we can see that the vast majority of financing has both a regional and a non-urban bias that leaves urban Africa on the margins.

So while African cities have been promised the fruits of the carbon markets in reality such projects make a tiny and insignificant part of infrastructure investment through the CDM. There are various discourses emerging from organisations such as the Cities Alliance and the World Bank that seek to ‘get cities prepared to attract carbon finance’ yet previous experience would suggest that such preparations are likely to include energy sector liberalisation, policy reform and cause future difficulties for African cities to address climate change, poverty and other imperatives.

These series of problems, flawed logics and failures characterising carbon financing are not going to address the energy, climate change and development challenges facing urban Africa. So where does this critique of carbon markets and current financing landscapes leave cities in terms of financing low carbon, resource efficient urban futures? As the Vice President of Tanzania made clear in his speech, industrial countries must pay and there must be an equitable and fair way to finance the transformation of infrastructure across urban Africa. This is financing based on the idea of climate debt, of paying for the historical pollution of the atmosphere and offering an alternative to the failed logics of markets in addressing these global inequalities that continue to characterise relationships between the continent and the North.

The need for municipalities across urban Africa to instigate significant investment programs becomes ever more important to address climate change, low carbon imperatives and the multiple development challenges facing these spaces of poverty and inequality. Yet, as the ICLEI conference illustrated again, there seems little in the way of alternatives to the limited, compromised and hopelessly flawed carbon financing mechanisms as countries of the North fail to undertake their historic responsibilities. It is time to pay the climate debt and support African cities to undertake different trajectories from the resource intense urban systems of the North. Many of these cities have yet to construct the required infrastructure systems needed over the next century, providing a limited window of opportunity to build a low carbon, resource efficient and fair urban future. The time for the global North to finance these transformations is now.

This blog is also available on the London School of Economics website and the Situated Urban Political Ecologies platform.